The Mango Tree Whispers

In the twilight hour, the mango tree stands like a sentinel at the edge of my grandmother's property—exactly as I remember it from childhood, yet somehow more imposing now. Twenty years have passed, but its gnarled trunk, rough as elephant hide, still bears the scars where my cousins once tried to hammer in makeshift steps. They abandoned their project halfway when Appachi caught them, her voice rising like thunder across the yard: "This is not for climbing! How many times must I tell you children?"

The house behind me sits empty, its blue paint peeling away to reveal the original yellow underneath, like skin shedding in the tropical heat. The windows are shuttered against intruders, but the mango tree needs no such protection. No one in the village would dare tamper with it, not even now when the property lies abandoned.

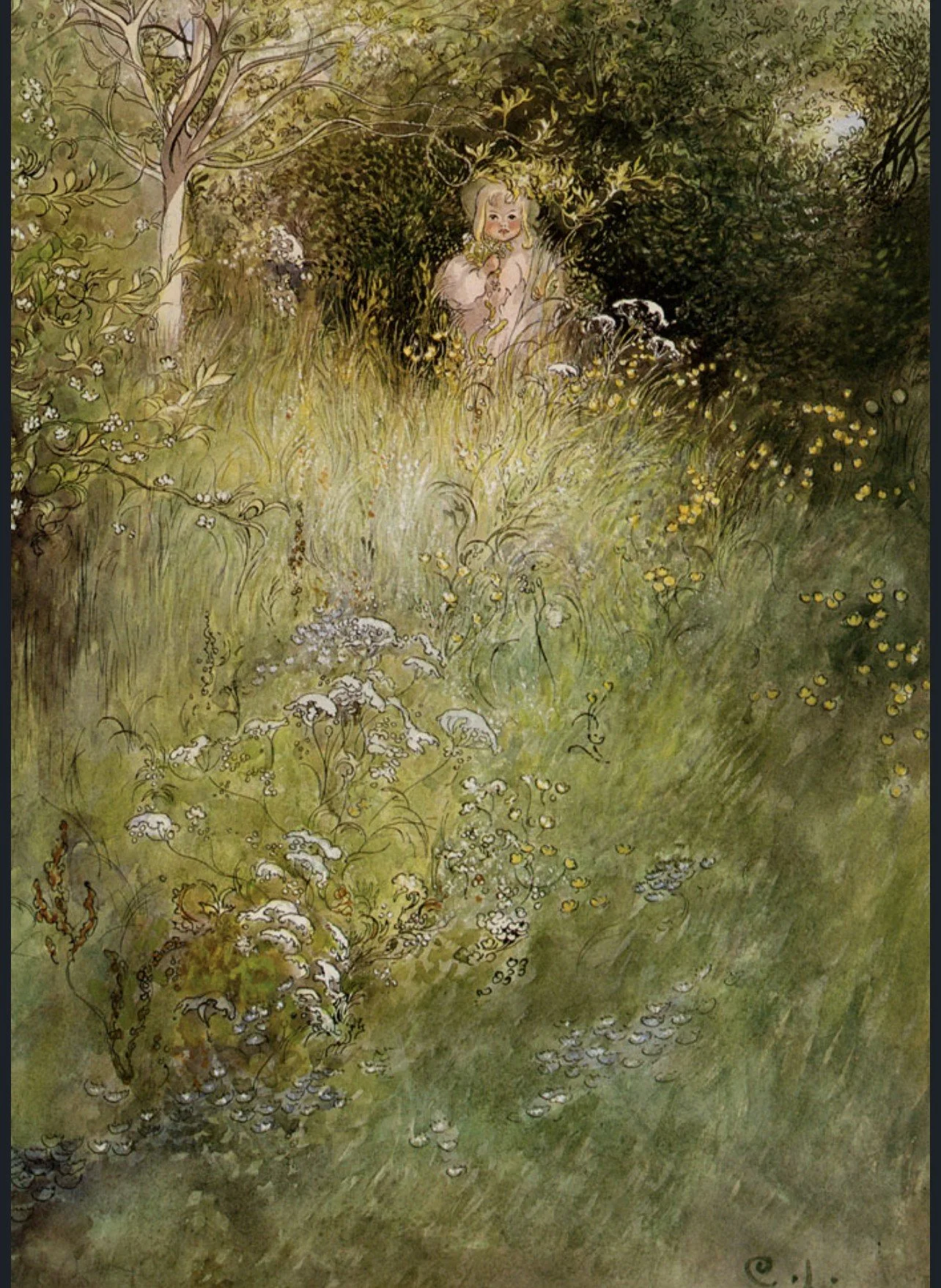

I set my bag down on the verandah and walk toward the tree, drawn by some unnamed gravity. My sandals crunch against the fallen leaves—brown, brittle things that whisper secrets with each step. The late afternoon sun filters through the dense canopy of green, creating patterns of light that shift and dance across the ground like spirits at play.

"Don't go near that tree after sunset," Appachi would warn, her eyes narrowing, voice dropping to a whisper. "The yakshini doesn't like to be disturbed when she's resting."

As a child, I imagined the yakshini—beautiful and terrible, with backward-facing feet and an insatiable hunger for mischief—perched among the highest branches, watching us with eyes that glowed in the dark. I pictured her long hair tangled in the leaves, her laughter disguised as rustling in the wind.

I never believed in spirits, not really. Yet standing here now, alone with the weight of memory pressing down on me like humidity before a storm, I can almost understand why the stories took root so deeply.

I. The Girl Who Would Not Listen

My grandmother's funeral was held three weeks ago in Toronto, where she had reluctantly relocated in her final years to live with my parents. "Old trees shouldn't be transplanted," she told me once, during one of our weekly phone calls. "They shrivel up and die." Her voice had carried the weight of someone who knew firsthand the truth of her words.

The lawyer handed me the keys to the property last week. "No one's lived there for almost a decade," he said, shuffling papers with disinterest. "Your grandmother was specific that it should pass to you upon her death." He hadn't mentioned why, and I hadn't asked. Some things, I've learned, reveal themselves in their own time.

I knew nothing of property management in rural Sri Lanka, even less about what to do with a house that had stood empty for years in the tropical climate. But something in me needed to see it one last time before deciding its fate—before developers could turn it into holiday cottages or before relatives who had never shown interest in Appachi suddenly discovered their deep attachment to her home.

The journey from Colombo took longer than I remembered, the roads narrower, the villages more developed yet somehow still frozen in time. When the taxi finally dropped me at the end of the lane, I stood staring at the metal gate for several minutes before pushing it open.

The garden, once Appachi's pride, had surrendered to wilderness. Jasmine vines strangled the fence posts, bougainvillea sprawled across pathways in riots of fuchsia and orange. But the mango tree—that stood unchanged, defiant against time and neglect, heavy with fruit that would soon fall with no one to harvest it.

As children, we were forbidden from collecting fallen mangoes. "They belong to her," Appachi would say, meaning the yakshini. "The ground offerings keep her satisfied." My cousins and I would watch from the verandah as overripe fruits splattered across the earth, their sweet scent attracting clouds of fruit flies. It seemed like such a waste then.

I fumble with the rusty padlock on the front door, finally forcing it open. Inside, the house smells of dust and absence. Sheets cover the furniture like shrouds, and the floorboards creak beneath my feet as though awakening from a long slumber. I open windows and doors, allowing light and air to enter again. The electricity isn't working—I'll need to call someone about that tomorrow—but I've brought candles and a flashlight, enough to get me through the night.

As I unpack my meager belongings in what was once my grandmother's bedroom, I glance out the window. The mango tree stands framed perfectly in the view, its uppermost branches brushing against the gathering evening sky. For an instant, I see something move among the leaves—probably a monkey or a bird—but my heart jumps all the same.

"Don't look directly at the tree after sunset," my cousin Lakshmi had once whispered to me. "She takes it as an invitation."

I shake my head at the memory and turn away from the window. These old superstitions have no place in my life now. I am thirty-four years old, with a doctorate in anthropology and a position at a university in Melbourne. I study cultural beliefs; I don't subscribe to them.

And yet, as darkness falls and I light candles around the house, I find myself avoiding looking out the windows facing the garden.

Dinner is simple—bread and cheese I brought from the city, washed down with bottled water. I sit on the verandah, watching fireflies dance in the garden. Their intermittent glow reminds me of childhood evenings spent listening to Appachi's stories while the adults talked politics and family gossip.

"The yakshini was once a normal woman," Appachi told us during one such evening. The scent of jasmine hung heavy in the air, mingling with the coconut oil in her long silver braid. "Beautiful beyond compare, with eyes like midnight and skin like honey. She fell in love with a man who promised to marry her, but he betrayed her with another."

We children leaned closer, drawn by the hushed tone of her voice.

"Mad with grief, she hanged herself from a mango tree—this very tree. But her spirit was too restless, too full of rage to move on. So she became a yakshini, bound to the tree where she ended her life, waiting to exact revenge on those who break promises."

"Is that why the tree only flowers every few years?" I had asked, always the curious one.

Appachi nodded solemnly. "It blooms when she forgives, when someone shows her kindness without expecting anything in return. But those times are rare."

Now, sitting alone on the verandah, I remember how the adults would exchange glances during these stories—half-amused, half-concerned that Appachi was filling our heads with nonsense. But they never contradicted her, not directly. Even those who claimed not to believe would still avoid the tree after dark. Just in case.

A sudden gust of wind rustles through the garden, causing the candle flames to flicker wildly. In the momentary darkness, I feel a presence beside me, as tangible as a hand on my shoulder. The air turns cool against my skin despite the tropical night.

Then the breeze dies down, the candles stabilize, and I am alone again.

Or at least, I think I am.

II. The Keeper of Memories

Sleep eludes me that first night. The house creaks and settles around me, the unfamiliar sounds of the countryside filtering through the open windows. Somewhere in the distance, a nightjar calls repeatedly, its plaintive voice echoing across the darkness.

I toss and turn on the narrow bed, my mind cycling through memories, regrets, and the thousand tasks awaiting me in the coming days. Around three in the morning, frustrated by my restlessness, I rise and light a candle.

The house feels different at this hour—more permeable somehow, as though the boundaries between past and present have thinned. I walk through the rooms, trailing my fingers along walls where photographs once hung, showing four generations of my family. Appachi had taken them all when she left for Canada, unwilling to leave behind these fragments of her life for dust and termites to claim.

In the kitchen, I open cupboards to find them surprisingly clean—someone must have been checking on the place occasionally. I make a mental note to ask the lawyer who has held this responsibility all these years.

A sudden noise from outside draws my attention—a heavy thud followed by a rolling sound. Setting my candle down, I peer through the kitchen window toward the garden.

In the faint moonlight, I can just make out the silhouette of the mango tree. Something—a fruit, perhaps—has fallen and rolled across the patchy grass. As I watch, another mango detaches and plummets to the ground.

This shouldn't be unusual. Mangoes fall when ripe; it's the natural order of things. Yet the timing feels deliberate, as though the tree is acknowledging my presence. A shiver runs down my spine despite the warm night air.

I turn away from the window, only to freeze at a sudden sound—soft, barely audible, but unmistakable.

Someone has whispered my name.

Morning brings clarity and rational thought. The whisper was surely the wind, or perhaps a bird with a call that resembled my name—the mind finds patterns where none exist, especially when primed by old stories and fatigue.

I busy myself cleaning the house, opening windows that have been sealed for years, sweeping dust into neat piles that I then dispose of in the overgrown garden. By midday, sweat soaks through my clothes, but the main rooms are at least habitable now.

A neighbor stops by—Mrs. Perera, who remembers me as a little girl. She brings me tea and rice, her face creased with smiles and curiosity.

"So, you'll be staying here now?" she asks, settling into a chair on the verandah. Her eyes constantly drift toward the mango tree, though she seems determined not to look at it directly.

"Just for a few weeks," I explain. "Until I decide what to do with the property."

She nods, sipping her tea. "Your grandmother was wise to leave it to you. You always understood the importance of this place."

The statement puzzles me. "Did she say that?"

Mrs. Perera smiles cryptically. "Some things don't need saying aloud to be understood." She sets down her cup with finality. "The tree is bearing well this year. Best crop in a decade."

I follow her gaze toward the mango tree, its branches heavy with fruit. "Yes, I noticed."

"But you haven't collected any." It's not a question.

"I only arrived yesterday," I reply defensively. "Besides, there's only so much mango one person can eat."

Mrs. Perera nods slowly, her expression unreadable. "Your grandmother always said the first mango of the season should be offered with respect." She rises to leave, pausing at the steps. "The electricity company should come by this afternoon. I called them for you."

Before I can thank her, she adds: "Don't stay out after dark. The power cuts have been frequent lately."

As she walks away, I can't help but feel she's left something important unsaid.

III. The Unheard Voice

That afternoon, while sorting through a chest of drawers in what was once my mother's childhood bedroom, I discover a small journal bound in faded red cloth. The pages are brittle with age, the ink faded to sepia. It takes me a moment to recognize Appachi's handwriting—more fluid in her youth, but with the same distinctive curl to her letters.

Most entries are mundane: records of rainfall, fruits harvested, visits from relatives. But scattered throughout are references to "She" or "Her"—always capitalized, always without further explanation.

"She seemed restless last night. The winds came suddenly."

"Offered the first mangoes today. She must be pleased—the air smells sweeter."

"Prema's child recovered after we placed her beneath the tree for an hour. She is merciful when approached with humility."

I sit back against the wall, journal open on my lap, unsettled by the matter-of-fact tone Appachi used when writing about what could only be the yakshini. It was one thing to tell children fantastical stories; it was quite another for a grown woman to document supernatural occurrences as casually as she noted the weather.

One entry in particular catches my eye, dated April 1965:

"Nalini refuses to respect the old ways. She laughs at the offerings, calls them wasteful superstition. I fear for her. Some disbelief is natural in youth, but mockery invites attention we do not want. Last night She whispered in the garden. I pretended not to hear, but I know She is watching my daughter."

Nalini—my mother. I try to imagine her as a young woman, rebellious and modern, chafing against village traditions. It's not difficult; she still speaks of her childhood with a mixture of fondness and relief at having escaped to a more cosmopolitan life.

The electricity technician arrives as promised, restoring power to the house with minimal fuss. He, too, keeps glancing at the mango tree while working, though he says nothing about it. When he leaves, I feel a strange relief at no longer being alone on the property, followed by an equally strange disappointment at having my solitude interrupted.

The day passes in a blur of cleaning and organizing. I find more letters tucked away in drawers, photographs slipped between the pages of books, forgotten relics of a life that continued long after my childhood visits ceased. Each discovery is both treasure and wound—evidence of years I missed with Appachi, conversations we never had, wisdom she might have shared.

As evening approaches, dark clouds gather on the horizon, promising one of the sudden, violent storms common in this region. I secure the windows and doors, leaving only the verandah accessible. Something about being completely sealed inside the house feels wrong, like breaking an unspoken agreement with the property itself.

The power fails just as the first fat raindrops begin to fall. One moment the ceiling fan is spinning lazily above me; the next, silence and stillness descend. Outside, the rain intensifies quickly, drumming against the roof in a deafening percussion.

I light candles and settle onto the verandah with a book, listening to the storm. The mango tree thrashes in the wind, its leaves turning silvery in the lightning flashes. Water cascades from its canopy like a waterfall.

Between thunderclaps, in that strange hollow silence that sometimes falls in the midst of storms, I hear it again—my name, called softly but distinctly. Not from inside the house or from the road, but from the direction of the tree.

The rational part of my mind immediately supplies explanations: the wind creating weird acoustics, my imagination working overtime, the power of suggestion from revisiting childhood superstitions. But another part—older, deeper, connected to this land in ways I've spent years denying—recognizes the voice.

It sounds like Appachi.

The storm passes as suddenly as it arrived, leaving behind a fresh, clean scent and puddles that reflect the emerging stars. The garden seems transformed, more vivid somehow, as though the rain has washed away a veil separating me from the true nature of this place.

I step off the verandah, drawn toward the mango tree. The wet grass soaks my sandals as I cross the garden, but I barely notice. My attention is fixed on the massive trunk, on the way moonlight filters through the leaves to create ever-shifting patterns on the ground.

Standing beneath its canopy, I feel simultaneously exposed and protected. Water drips from leaves overhead, landing on my upturned face like cool fingers.

"I'm here," I say softly, feeling foolish yet compelled to speak. "What do you want from me?"

Only silence answers—the special quality of silence that follows rain, pregnant with possibility.

I reach up to touch a low-hanging branch, running my fingers along rough bark still slick with rainwater. "Appachi sent me here for a reason, didn't she?"

A sudden breeze shakes the branches, sending a shower of droplets down upon me. And there—unmistakable this time—a whisper that seems to come from everywhere and nowhere:

"Remember."

I stumble backward, heart pounding. My foot catches on something solid, and I nearly fall. Looking down, I see a perfect mango lying on the ground—golden-yellow with a blush of red, exactly the kind Appachi preferred.

With trembling hands, I pick it up. It's warm to the touch despite the cool night air, its skin smooth and unblemished. Not bruised from falling, not pecked by birds. As if it had been gently placed there for me to find.

In that moment, standing beneath the mango tree with fruit in hand, I feel the years collapse between us—between the woman I've become and the girl who once believed in spirits that guarded ancient trees. Between the academic who studies cultural beliefs as artifacts and the grandchild who absorbed those beliefs like sunlight.

"I remember," I whisper back, though to whom, I cannot say.

IV. The Gift of the Tree

That night, clutching the mango close to my chest, I dream of Appachi. Not as the frail woman who departed for Canada with reluctance etched into every line of her face, but as the formidable matriarch of my childhood—tall and straight-backed, her silver-streaked hair falling to her waist when unbound.

In the dream, we sit beneath the mango tree, its branches heavy with fruit and flowers simultaneously, an impossible abundance. Appachi peels a mango with practiced hands, the golden flesh glistening in dappled sunlight.

"You were always the one who listened," she says, offering me a piece. "Even when you pretended not to believe."

"I didn't understand," I tell her, accepting the fruit. Its sweetness floods my mouth, more intense than any mango I've tasted in waking life.

"Understanding isn't necessary for respect." She looks up into the branches. "She doesn't demand belief—only acknowledgment."

"The yakshini?"

Appachi smiles, neither confirming nor denying. "There are older things in the world than your textbooks can explain, child. Things that remember when promises are kept and broken."

A breeze rustles through the leaves, carrying with it a whisper too faint to distinguish.

"What is she saying?" I ask.

But Appachi only shakes her head, her form growing translucent as the dream begins to dissolve around me. "Listen with more than your ears."

I wake clutching the perfect mango, its warmth unchanged, its scent filling my bedroom like incense. Outside my window, the first light of dawn illuminates the garden, catching the dew-drenched leaves of the mango tree.

For the first time since arriving, I feel certain of my purpose here.

The next morning, I wake with purpose. The mango sits on my bedside table, still perfect, still emanating that subtle warmth. I dress quickly and walk to the village market, returning with flowers, incense, and a small clay lamp—items for a simple puja that Appachi taught me to perform long ago.

Mrs. Perera watches from her garden as I arrange these items at the base of the mango tree. She nods approvingly but doesn't approach.

I light the incense and lamp, placing the flowers in a small circle. Then I add the mango, setting it carefully among the blossoms. The ritual feels both foreign and familiar, like speaking a language I haven't used since childhood but find I still remember.

"I don't know if you're there," I say quietly, addressing the tree, the air, the memory of my grandmother, or perhaps the yakshini herself. "I don't know if any of the stories are true. But this place was important to Appachi, and now it's my responsibility."

A gentle breeze stirs the leaves overhead, carrying the scent of incense upward.

"I'm not staying," I continue. "I have a life elsewhere. But I won't sell this land or let it be developed. I'll find someone to care for it—for you—properly."

As I speak these words, I realize they are true. The thought of strangers living here, of the mango tree being cut down to make room for modern conveniences, fills me with visceral dread. This place may not be my home anymore, but it remains part of me in ways I'm only beginning to understand.

I remain seated beneath the tree for nearly an hour, lost in memories and possibilities. When I finally rise to leave, I notice something extraordinary.

A single blossom has appeared on one of the lower branches—delicate, pale yellow against the dark green leaves. Impossible, given that mango trees don't flower when heavy with fruit.

Yet there it is—a single bloom out of season, like a response to my promise.

V. The Return of Memory

That afternoon, I find myself drawn to the small storage shed at the far end of the garden—a place forbidden to us as children, ostensibly due to rusty tools and the potential for injury. Now, as I approach it with adult eyes, I wonder if there wasn't another reason for keeping us away.

The padlock is so corroded it breaks off in my hand when I tug at it. Inside, dust motes dance in the shafts of light penetrating through gaps in the wooden walls. The space is surprisingly tidy—shelves along one wall hold garden implements, clay pots, bags of long-desiccated soil. But it's the back wall that draws my attention.

A small altar sits on a shelf, so simple it might be overlooked—a tarnished brass plate holding the remnants of what might once have been flowers, a blackened oil lamp, and a framed photograph so faded it's difficult to make out the subject. I step closer, squinting in the dim light.

The photograph shows a young woman in a traditional sari, her hair loose around her shoulders, her smile radiant. Something about her features seems familiar, though I'm certain I've never seen her before. I gently wipe dust from the glass with my thumb, revealing more detail—high cheekbones, determined chin, eyes that seem to hold both joy and sorrow.

"You've found her, then."

I start at the voice, nearly dropping the photograph. Mrs. Perera stands in the doorway, silhouetted against the afternoon light.

"I'm sorry," I stammer. "I was just exploring—"

"No need for apologies." She steps into the shed, taking the photograph from my hands with reverence. "Your grandmother would have wanted you to know eventually. That's why she left this place to you, I think."

"Who is she?" I ask, though some part of me already suspects the answer.

Mrs. Perera studies the photograph before responding. "Her name was Malini. She lived in this house before your grandmother's family purchased it. Some say she still does."

A chill runs down my spine despite the close heat of the shed. "The yakshini?"

Mrs. Perera nods slowly. "The stories have grown more elaborate over time, as stories do. But the truth is simple enough. Malini loved unwisely, was betrayed, and took her own life beneath the mango tree that her father had planted on her birth. Whether her spirit lingers there or whether that's just what grief-stricken people tell themselves to make sense of tragedy—who can say for certain?"

She replaces the photograph carefully on the altar. "Your grandmother maintained this place even after everyone else had forgotten. She believed Malini deserved to be remembered with dignity, not just as a cautionary tale for disobedient children."

"But the whispering, the strange occurrences—"

Mrs. Perera shrugs. "Some things defy explanation. I've lived next door for sixty-three years and seen enough to keep an open mind." She glances at me shrewdly. "You've heard something too, haven't you?"

I hesitate before nodding. "My name. And... I think I heard Appachi's voice during the storm."

"Ah." She doesn't seem surprised. "The tree has always been most active during storms. Your grandmother believed it was because electricity in the air makes the veil between worlds thinner." She smiles at my expression. "Not all educated people reject what they cannot explain, you know. Your Appachi read more books than anyone in the village, yet she never doubted what she experienced."

As we step out of the shed, closing the door behind us, Mrs. Perera points to the mango tree. "Look there—at the lowest branch on the eastern side. Do you see that mark?"

I follow her gesture and notice a peculiar scar in the bark—not unlike a handprint pressed into clay.

"That appeared the morning after Malini died," Mrs. Perera says softly. "Some say she grabbed the branch to break her fall at the last moment—a final instinct for life even as she chose death. Others believe it was a message, a promise to remain connected to this world." She pauses. "Your grandmother touched that mark every morning when she thought no one was watching."

The revelation settles over me like evening fog—not obscuring truth but transforming it into something more nuanced than mere fact or fiction.

"Thank you for telling me this," I say finally.

Mrs. Perera pats my arm. "Stories need keepers, child. Even the sad ones—especially the sad ones. Otherwise, how do we learn?"

As she walks away, I turn toward the house, feeling the weight of generations watching me from windows, from tree branches, from the spaces between what we know and what we sense.

Over the next week, more strange occurrences follow. Items I'm certain I left in one room appear in another. The scent of jasmine fills the house at odd hours, though the vines outside are not yet in bloom. At night, I sometimes wake to the sound of someone humming a lullaby Appachi used to sing.

I should be frightened, but instead, I find these manifestations comforting—as though the house itself is revealing secrets, showing me what it wants to become.

VI. The Promise Keeper

On my third night, I dream of the young woman from the photograph—Malini. We walk together along a path that doesn't exist in waking life, bordered by flowering trees that bloom and fruit simultaneously, defying natural order.

"You don't look like her," I say, meaning the fearsome yakshini of childhood stories.

Malini laughs, the sound like water over stones. "People see what they expect to see. Fear makes monsters of memories."

"Are you real?" I ask, immediately embarrassed by the bluntness of the question.

She considers this seriously. "What is real? The tree is real. The earth beneath it is real. The stories people tell about me are real in their consequences." She reaches out to touch a branch, and flowers bloom beneath her fingers. "Perhaps I am just the meaning people make of tragedy. Perhaps that's real enough."

"What do you want from me?" I ask as the dreamscape begins to shimmer around us.

She turns to me, her eyes reflecting impossible light. "The same thing your grandmother wanted—someone who remembers without fear."

The dream dissolves, but her words linger as I wake to early morning birdsong filtering through my window. Outside, the mango tree stands bathed in golden light, its fruits glowing like lanterns among the leaves.

That afternoon, browsing through Appachi's remaining books, I find a slim volume of local history tucked between agricultural manuals. Inside is a newspaper clipping from 1923, yellowed and fragile:

"TRAGEDY AT WELIGAMA ESTATE: Young Woman Takes Own Life The daughter of prominent landowner S.P. Jayawardene was discovered yesterday morning beneath the family's prized mango tree, the apparent victim of suicide by hanging. Miss Malini Jayawardene, 19, had recently broken her engagement to Mr. Clarence Perera of Colombo. No note was discovered, though sources close to the family report the young woman had been despondent in recent weeks. The funeral will be held privately. The family requests privacy during their time of mourning."

The clinical brevity of the report feels obscene compared to the weight of the tragedy it describes. No mention of dreams destroyed, promises broken, or the ripples of grief that would spread outward for generations. Just a few lines recording the end of a young woman's life, reduced to a sensational headline and quickly forgotten by all but those who loved her.

In that moment, I understand what Appachi wanted me to remember—not just Malini's tragedy, but her humanity. Not just the cautionary tale, but the person behind it. Not just the fearsome yakshini who punishes oath-breakers, but the woman who loved too deeply and paid too dearly.

Mrs. Perera introduces me to her daughter's family, who need a place to live while saving money to build their own home. They are respectful, quiet people who listen wide-eyed when I tell them about the mango tree's significance. They promise to continue the offerings, to never cut branches without permission, to teach their children the story of the yakshini who protects those who honor her.

When I ask what rent they can afford, the young woman—Priya—looks embarrassed. But before she can speak, I hear that whisper again, clear as daylight: "Remember kindness."

"There's no rent," I hear myself saying. "Just care for the place as if it were your own, especially the mango tree."

The relief and gratitude on their faces tell me I've made the right decision.

"There's one more thing," I add, surprising myself. "In the storage shed, there's a small altar. It needs to be maintained—fresh flowers, an oil lamp lit on full moon nights. Can you do that?"

Priya nods solemnly. "Of course. We understand the importance of respecting those who came before."

That evening, I sit beneath the mango tree with Appachi's journal open in my lap, reading entries spanning decades—records of storms weathered, harvests gathered, children born, elders passing. Throughout it all, the mango tree stands as a constant, its cycles of flowering and fruiting marking time more reliably than calendars.

In her later entries, as arthritis made her handwriting increasingly shaky, Appachi wrote more explicitly about the yakshini—not as a fearsome spirit, but as a guardian, a witness, a keeper of promises.

"She has watched over us for generations. Not in malice as the stories claim, but in vigilance. She reminds us that words have power, that promises matter, that respect for the past shapes our future. I have entrusted Malini's memory to the one grandchild who might understand—my little anthropologist who questions everything yet listens with her heart. When I am gone, she will know what to do."

The words blur as tears fill my eyes. I trace the faded ink with my fingertip, feeling connected to Appachi across time and distance, understanding at last what she tried to teach me all those years ago—that some truths can't be analyzed or categorized, only experienced and honored.

As twilight deepens around me, a breeze stirs the leaves overhead. But this time, no whisper follows. Instead, I feel a profound sense of peace, as though something long disturbed has finally found rest.

VII. The Tree that Remembers

On my final evening, I sit beneath the mango tree as the sun sets, feeling a strange mixture of sadness and fulfillment. Tomorrow I'll return to my life in Australia, to classrooms and research papers and colleagues who would raise skeptical eyebrows at what I've experienced here.

"I'll come back," I promise the gathering darkness. "Not to stay, but to visit. To remember."

The breeze picks up, carrying with it the scent of earth and growing things. In the failing light, I notice something at the base of the tree where I left my offerings days ago. The flowers have withered, the incense burned down to ash, but the mango—the perfect, warm mango—is gone.

In its place lies a small silver anklet, tarnished with age. I recognize it immediately as one Appachi showed me once, claiming it had belonged to her grandmother. It had disappeared years ago, prompting accusations among household staff and family members. We never found it despite thorough searching.

With shaking hands, I pick it up. The metal warms quickly against my palm, almost as though it's been waiting for me.

And I understand at last what Appachi wanted me to remember—that some bonds transcend rational explanation, that some places hold memories thicker than blood, that sometimes the stories we dismiss as childish fantasy contain deeper truths than our educated minds can comprehend.

The yakshini may be real or metaphor; it hardly matters now. What matters is the promise kept, the connection maintained, the respect shown to things we don't fully understand.

I slip the anklet into my pocket and stand, brushing dirt from my clothes. As I walk away from the mango tree toward the house, the evening breeze follows me like a gentle hand at my back.

Before leaving the next morning, I place the anklet in Priya's hands, explaining its significance. Her eyes widen as she accepts it, clearly understanding the trust being placed in her.

"I'll return it to you when you visit," she promises.

"Keep it near the tree," I tell her. "It belongs here more than with me."

As my taxi pulls away from the gate, I look back at the property—the blue house with its peeling paint, the overgrown garden that will soon be tamed by caring hands, and the mango tree standing tall against the morning sky.

In my academic papers, I've often written about the function of folklore in creating community cohesion, in transmitting cultural values across generations. Cold, analytical language that reduces rich traditions to sociological mechanisms. Now, I wonder how I'll write about such things in the future, knowing what I know, having experienced what I've experienced.

Perhaps I won't try to explain at all. Perhaps some things are meant to be preserved rather than dissected—honored rather than understood.

Back in Melbourne, I find myself changing small habits. I place flowers on my windowsill during full moons. I whisper thanks before eating particularly sweet fruit. I listen more carefully to the wind.

Colleagues notice a shift in my teaching approach. "You seem more... open lately," one remarks after I guide a class discussion about indigenous spiritual practices without once using the words "superstition" or "pre-scientific worldview."

"Let's just say I've learned that knowledge takes many forms," I reply.

Six months later, an envelope arrives from Sri Lanka. Inside is a photograph of the mango tree, now surrounded by well-tended plants. In the foreground stands Priya's family, smiling beneath the spreading branches. The tree is in full bloom—an impossibility given the season, yet there it is, documented in living color.

Scrawled on the back in Priya's careful handwriting: "The tree remembers your promise. So do we."

I place the photograph on my desk, where morning light catches it first thing each day. Sometimes, in the quiet moments before my day begins, I swear I can smell mangoes ripening in the sun, hear leaves rustling in a distant breeze, feel the weight of watchful eyes—benevolent now, at peace.

And just for a moment, I hear Appachi's laughter in my memory.

Hafsa Rizvi

Hafsa Rizvi is a writer and storyteller from Sri Lanka who finds meaning in quiet moments, tangled roots, and tales passed down through generations. She writes to preserve memory, culture, and the fragile beauty of everyday life. Her work often explores themes of identity, belonging, and the subtle magic hidden in the ordinary.